The ‘future’ city finds its inspiration in a philosophical, psychological and/or sociological concept, and its aim is to determine a living place for a new society in times to come. The visionary thinker looks ahead, see things, and anticipates the unexpected. The concept of a future city must include all the best of the present, which will be projected towards unknown ages. Fantasy is the abstract engine to look ‘beyond architecture’ and create strange and unfamiliar compositions (BINGHAM et al, 2004).

The visionaries Piranesi (1720 – 1778) and Boullée (1728 – 1799) stand out as early representatives of dream-like architecture projected into the future. Both architects have been encountered earlier because of the exceptional character of their work. The etchings of Piranesi of ancient Greek and Roman sites, produced at the end of the eighteenth century, stirred the imagination of ‘Romantic’ viewers. Piranesi depicted a haunted world, which pointed to darkness and oblivion.

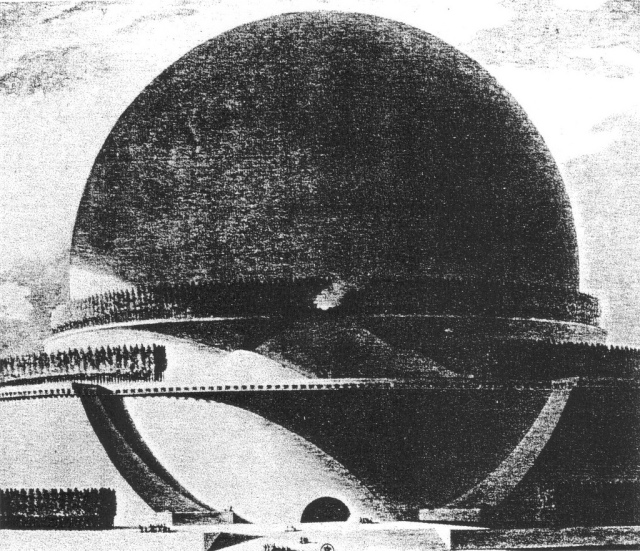

Fig. 656 – The elevation of a cenotaph dedicated to Sir Isaac Newton as given in a drawing by Boullée in 1784.

The other site of the coin is the optimism of Etienne-Louis Boullée with his abstract geometric style, which was inspired by Classical forms. Boullée’s most notable work was a series of drawings made between 1778 and 1788. Futuristic designs as a Metropolitan Church (1780), City gate with guns (1780), a Square Temple (1780), and later his Cénotaphe a Newton (1784) (fig. 656) and the Deuxième projet pour la Bibliothèque du Roi (1785) made his name as a visionary. His book ‘Architecture, essai sur l’art’ (Essay on the Art of Architecture) was published for the first time by Helen Rosenau in 1953.

Scores of fantastic and/or idealistic thinkers followed these two futuristic architects in the early nineteenth century. They grabbed the widening of conceptual space created in higher division thinking. This collective event did not only occurred in architecture, but also in science – with new forms like sociology, psychology, geology and astronomy – and in the understanding of art (history).

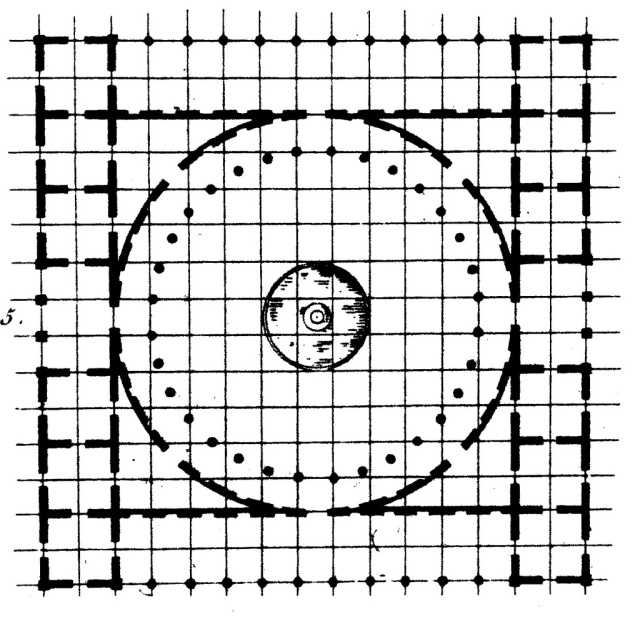

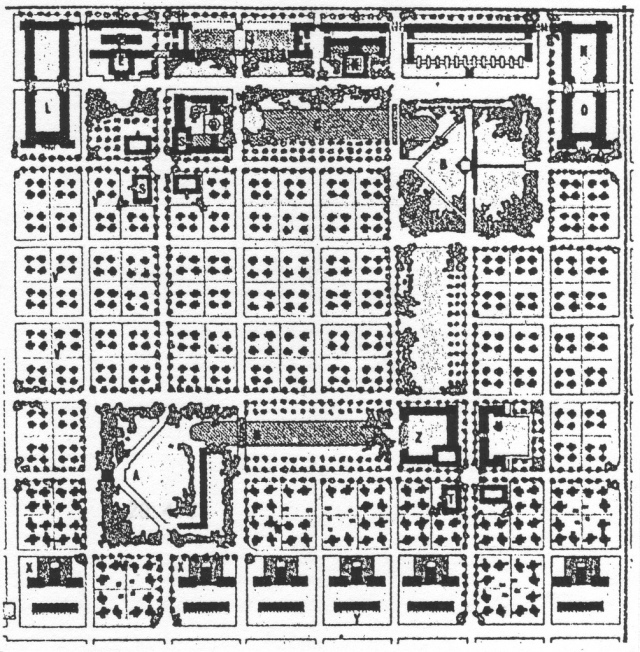

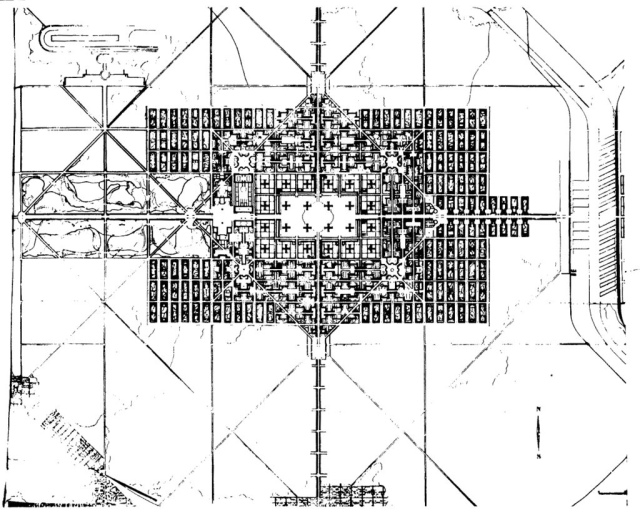

Jean Nicolas Louis Durand (1760 – 1834) was a pupil of Boullée, who vulgarized his message. His book ‘Précis des leçons d’architecture données à l’école polytechnique’ (1802-1805) was translated in German and Italian and became a reference point for the new way of building (KAUFMANN, 1985). Durand attacked the Saint Peter, its square and the Pantheon in Paris and gave them as examples how not to build. There is, in his view, no point of useless decoration, but craftsmanship should be found in the construction alone. The main aim of architecture is its usefulness, not it’s liking. His plates on the ‘mecanisme de la composition’ make clear that his creativity was guided by a grid-like pattern (fig. 657).

Fig. 657 – This plate indicates the grid-like approach as a mechanism of composition (‘Mécanisme de la composition’). It was proposed by Durand in his book Précis des leçons d’architecture données à l’école polytechnique’ (1802 – 1805). The grid is a marker of the Fourth Quadrant and can be interpreted as a means to organize multiplicity.

Durand’s ‘scientific’ method highlights the end of an era in which classical proportions dominated the idea of beauty in architecture. In his ‘Recueil’ (1799/1801) he used an a posteriori method to define his types. By doing so, he became a protagonist of functionalism – an architectonic doctrine that put the emphasis on practical considerations such as use, material, and structure, rather than a preconceived plan of the architect. The logic of construction and geometry resulted, in Durand’s view, to attractiveness and not a search for beauty itself.

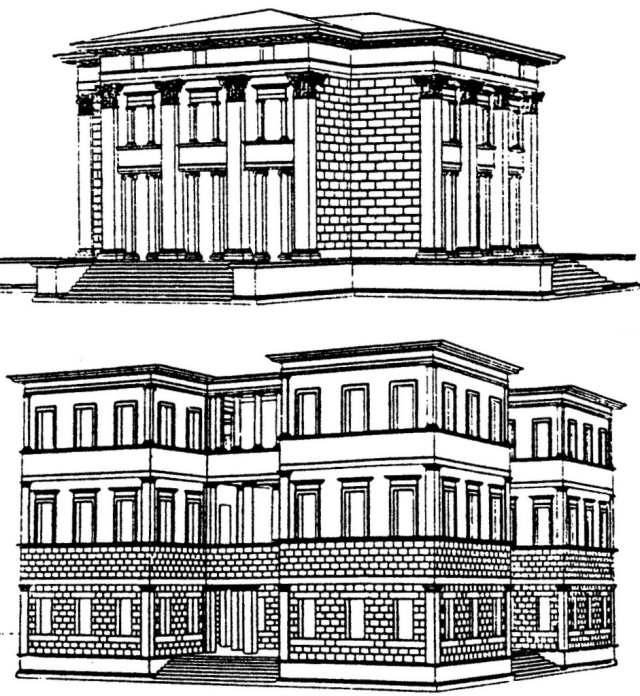

Louis Ambroise Dubut (1760 –1846) was another architect of that same period. He presented his work, called ‘Architecture Civile. Maisons de Ville et de Campagne en Toutes Formes et de Tous Genres..,’ (1803), in fifteen parts. Further editions in 1837 and 1842 indicated its popularity. Dubut was a pupil of Ledoux, and his designs elaborated on the useful components of the experiments during the Revolution. Dubut approached the (future) city not as a mental entity (unity), but tried to give examples, which could form a city in the process. He gave, for instance, about fifty examples of various houses, which were numbered (fig. 658).

Fig. 658 – The houses No. 10 (above) and 14 (below) were some of the examples given by the French architect Louis Ambroise Dubut in his search for the elements of a future city. Square and circular plans explored the cognitive ground, which was broken in the nineteenth century. Its associated aesthetic experience set the trend for architecture to come.

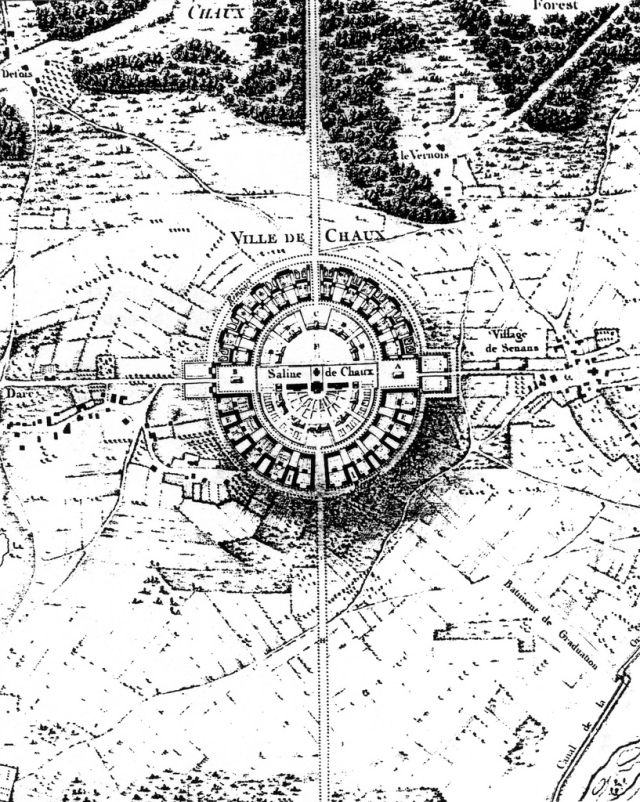

A most noticeable futuristic enterprise, which was partly realized, is found in eastern France in the Jura Mountains (France-Comté). The architect Claude Nicolas Ledoux planned here between 1775 – 1780 the Royal salt works between the villages Arc and Senans and called the new town Chaux. Ledoux (1736 – 1806) was an architect, who made his career in the years before the French Revolution by building houses for the rich (like the Pavillon de Louveciennes) and for working for the government.

The Hôtel Thélusson in the Rue de Provence in Paris was built between 1778 and 1781 and was the largest of Ledoux’s private commissions to be realized. It was a mixture of a palace and a pavilion and can be regarded as a folie in its most elaborate form. The palace, designed after Ledoux’s work in Saline de Chaux, was a city in miniature complete with boulevards, natural scenery and grottoes. The rear yard had a theatrical nature, which reminded to the plan of Saline. The hated toll houses around Paris (1784 – 1789, see fig. 502) were also part of Ledoux’s oeuvre.

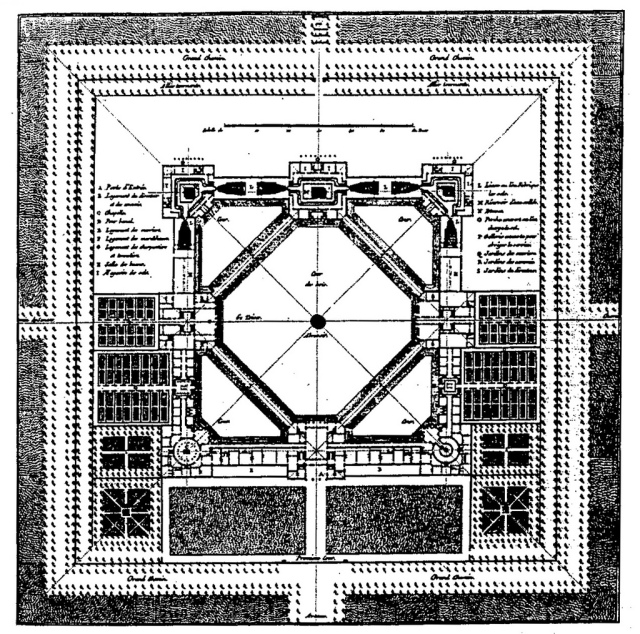

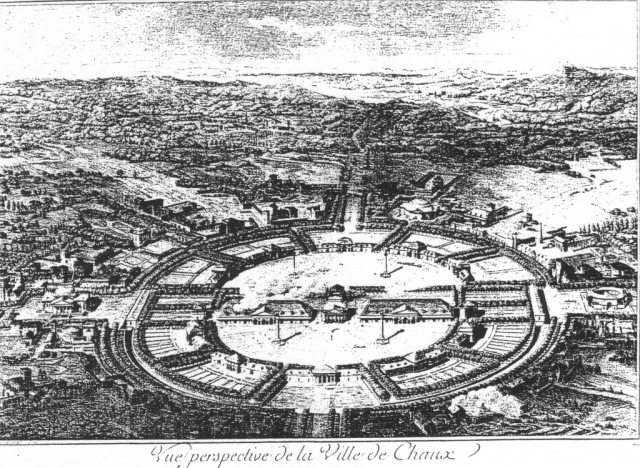

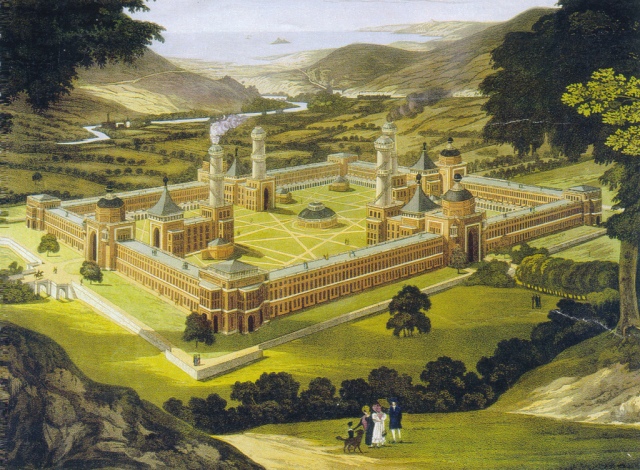

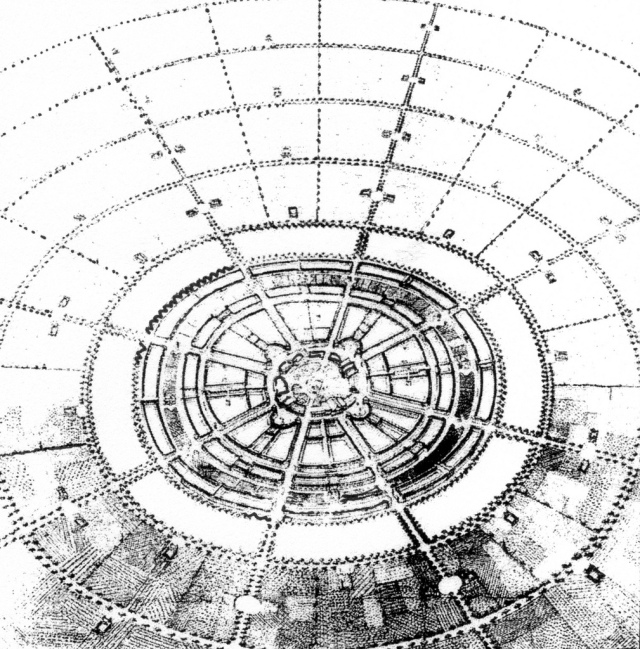

The French Revolution of 1789 brought him nearly to the guillotine, but he was spared and allowed to retire. Subsequently, he continued to work on the visionary city of Chaux, which was started in 1780 as a side project of his activities in Arc-et-Senans. The first drafts of the town were presented to Turgot in 1775, but constantly perfected afterwards. An amended version was published eventually in 1802 in a book titled ‘L’Architecture considerée sous le rapport de l’art, des mœurs et de la legislation’ (Architecture considered in relation to art, morals, and legislation). It contained a collection of his designs (fig. 659 – 661).

Fig. 659 – The first project for the salt works of Chaux (France) by Claude-Nicolas Ledoux, 1773 – 1774, had a square layout. His plan was ‘conform to the needs and conveniences of a productive factory where the utilization of time offers a first economy’.

Fig. 660 – The Saline de Chaux, situated between the villages Arc and Senans (Doubs), as seen in a revised, second project. The circular form pointed to a ‘theater of work’, following the layout of classical theaters. These ideas were contemporaneous with Antoine Petit’s project for a Hotel-Dieu (1774; see fig. 347) and predated the panopticon prison of the English reformer Jeremy Bentham (1797; see fig. 363) by some twenty years. Only some of the buildings in the central court of Chaux – including the house of the director – were completed.

Ledoux used the ‘rhetorical power of forms and ornamental elements’ to reduce the classical language (MALLGRAVE, 2005). In fact, he wanted to create a ‘modern classicism’ by using his knowledge of the classical orders and reinvent them in a theatrical setting (VIDLER, 1990). The products of this exercise are fairly heavy and emphatic. They do not particular appeal to modern aesthetic feelings, but Ledoux must still be regarded as the first ‘Fourth Quadrant’ architect – reworking architectural history into a new reality guided by feelings and sentiments.

Fig. 661 – A perspective view of Chaux as given by Ledoux showed a circular layout, as it was conceived in 1774. The House of the Director and side buildings are situated on a horizontal axis in the center.

The House of the Director and side buildings at Chaux (Photo: Marten Kuilman, Dec. 2010).

Human feelings became more and more an important factor in the growing industrialization of Europe. A massive surge of activity had set in at the end of the eighteenth century – and became known as the Industrial Revolution.

Jean-Baptiste Say pointed in his book ‘Traité d’économie politique’ (1803) to the advantages of industrialization and progress, which took place in England, and suggested that France should follow the same course. The sometimes appalling circumstances for the workforce gave rise to different forms of socialism. The idealistic capitalists aimed – in a patronizing way, but with good intentions – at better living standards for the laborers. This very mixture of human concern and the (grim) face of multiplicity is typical for a Fourth Quadrant situation in a communication.

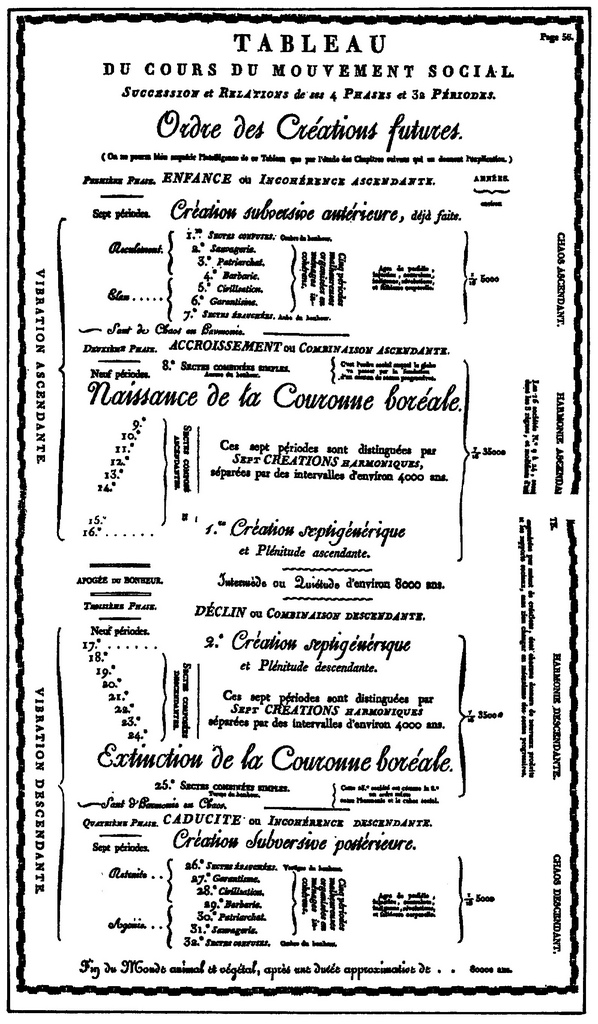

The confusing situation at the beginning of an era of wider division thinking (1800) was expressed in France by Charles Fourier (1772 – 1837). His critical view on society was given in his book ‘Théorie des quatre mouvements et des destinées generales (Theory of the four movements and the general destinies), which appeared anonymously in Lyon in 1808. A recent edition (STEDMAN JONES & PATTERSON, 1996) makes this work more accessible and is, in fact, the first translation of Fourier’s writings in the English language, except for a fourteenth page pamphlet in 1827 and a selection of Fourier’s work translated by Julia FRANKLIN (1901).

The title of the book suggests a four-fold way of thinking, but the reader will be disappointed. The ideas of the traveling salesman Fourier were focused on cooperation as a means to social success. People should be housed to-gether in ‘phalanxes’ – self-contained communities consisting of sixteen hundred people working together for mutual benefit. He was a supporter of women’s rights (inventor of the word ‘feminism’) and liberation of human passions.

Fig. 662 – Fourier’s scheme of social movement – as given in his book ‘Théorie des quatre mouvements et des destinees generales’ (1808) exhibits the exuberance of a mind let loose in the Fourth Quadrant of the European cultural presence.

The book is concerned with feelings and harmonic passions and points to the Fourth Quadrant qualities of the visible invisibility. The four movements of the book title relate to the material, organic, animal and social world. The four cardinal passions were in his view: friendship (in childhood), love (in youth), ambition (in maturity) and familism (blood affiliation, in old age). His universal-historic order of creation (‘ordre des creation futures’) consisted of four periods, but other types of division are also used. His ‘apogee du bonheur’ (culmination of happiness), with a duration of about 8000 years, right in the middle, suggests that Fourier’s basic line of thinking was dualistic (fig. 662).

Fourier’s books were a weird collection of ideas and schemes, with the four-fold thrown in as a numerological tool among other types of divisions. However, his (di)visions were an inspirational source for socialists in times to come. Fourier used the mental space, which was created by the introduction of higher division thinking in the cultural history of Europe around the year 1800, in a remarkable way. It was for the first time since the twelfth century that multiplicity was embraced so wholeheartedly. The man-and-wife team MANUEL & MANUEL (1979, Chapter 27) was more critical in their verdict on his achievements: ‘Paranoid elements are always latent in the great structure-builders; in Fourier they rise to the surface – nothing is hidden.’

Charles Fourier saw himself as part of a great tradition when he noticed the difference in the price of apples in Paris and the countryside: ‘There had been four apples in the world: two were destined to sow discord and two to create concord. While Adam and Paris had brought misery to mankind, Newton’s apple had inspired the discovery of the basic law of attraction, which governs physical motion, and its complement, Fourier’s apple, had moved him to formulate the law of passionate attraction, which would inaugurate universal happiness.’ These grotesque ideas are charming observations on the borderline of division thinking and numerology.

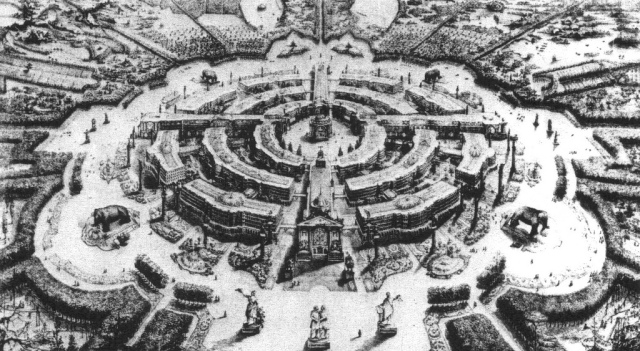

Fig. 663 – This plan by André of a community based on ‘equality, liberty and unity’ follows ideas of Charles Fourier’s ‘garantiste’ city.

The architectonic ideas of Fourier on a future city of happiness were not specified in his book ‘L’Harmonie universelle et le phalanstère’ (1822). His attention to building was more directed towards a social system. Some of his followers visualized his communities (‘phalanxes’ or ‘garantiste’) as real cities (fig. 663). John Minter Morgan (1782 – 1854) used a drawing of a utopian settlement as a frontispiece of his book ‘The Christian commonwealth’ (1845) depicted as a square with a central building.

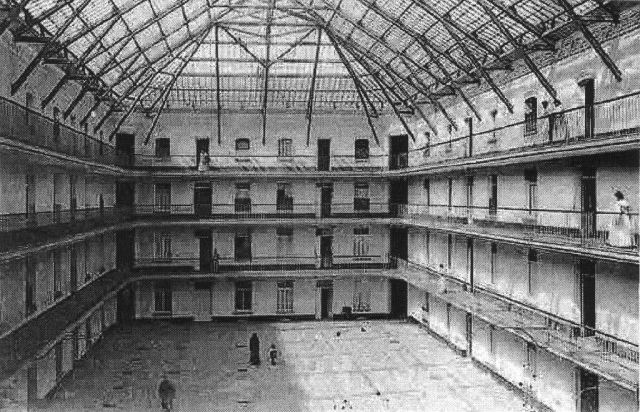

The Familistère is a housing complex in Guise (Picardy, Northern France), which was actually built (fig. 664). It was initiated in 1859 by the industrialist Jean-Baptiste Godin (1817 – 1888) to accommodate his laborers of his factory. Godin followed ideas of Saint-Simon and Fourier’s Phalanstère.

Fig. 664 – The interior of a housing complex for labourers of Jean-Baptiste Godin’s ironworks in Guise (Picardy, Northern France).

The manufacturer Robert Owen (1771 – 1858) became known as a social reformer when he improved the New Lanark mills in Lanarkshire (Scotland) with better housing and education of the young. He paid four month wages to the workers during an embargo against the United States in the War of 1812 when the cotton mill was closed. Owen did not believe in religion, but invented a creed himself. It was based on the assumption that man’s character is made not by him but for him. Circumstances over which he had no control formed the base of his being.

Owen emphasized in his book ‘Revolution in the Mind and Practice of the Human Race’ (1849) that the human character is formed by a combination of Nature and God and the circumstances of the individual’s experience. His book was a response to the European political upheavals of 1848 when the Paris Commune started and Marx and Engels published their ‘Communist Manifesto’, but it was also a recapitulation of his ideas on social reform. He was against the use of violence in the revolutionary process, because it mimicked the errors of their enemies instead of resorting to reason and kindness.

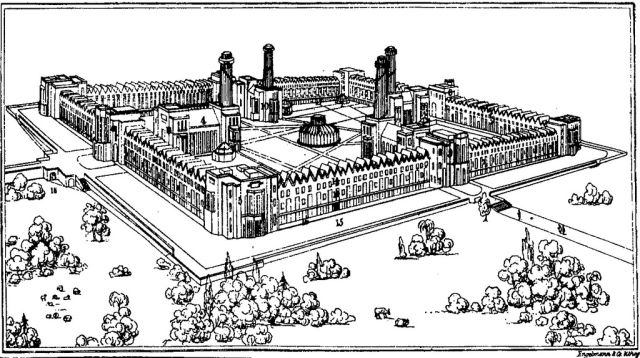

Robert Owen moved to America when his Scottish experiment got entangled in economic objections by his fellow directors. They regarded his social measures damaging for the profits. Owen purchased in 1825 the existing German religious community called ‘Harmonie’ in Southern Indiana. This prosperous settlement was started in 1814 by Father Johann Georg Rapp (1757 -1847), founder of the Harmonists or the Harmony Society. Soon it was called ‘New Harmony’ and was to become a ‘communistic’ town of work and education under the guidance of Owen (fig. 665) (ROYLE, 1998).

Fig. 665 – The town of ‘New Harmony as envisioned by Owen’ was given by the architect Stedman Whitwell (1784 – 1840) in his ‘Design for a Community of 2000 Person founded upon a principle Commended by Plato, Lord Bacon and Sir Thomas More’, printed in London in 1830.

The social experiment lasted some four years, because ‘it seemed that the difference of opinion, tastes and purposes increased just in proportion to the demand for conformity’ and ‘it appeared that it was nature’s own inherent law of diversity that had conquered us… our ‘united interests’ were directly at war with the individualities of persons and circumstances and the instinct of self-preservation’ (as noted by the individual anarchist Josiah Warren in 1856).

New Harmony remained a center of scientific research despite its failed utopian aims. The early headquarters of the U.S. Geological Survey was based in New Harmony, resulting in a large geological and natural science collection, which later became incorporated in the Smithsonian Institute. David Dale Owen (a son of Robert) turned to geology under the influence of William Maclure (1763 – 1840). The latter was president of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia for twenty-two years. Maclure produced the first geological map of America in 1809, which is six years earlier than a similar map of England by William Smith.

The Cadbury Brothers in Birmingham (England) started to educate the illiterate and poor workers and their children of their chocolate factory in the same year (1859) as Godin set out his Familistère in France. A feeling of compassion struck into the minds of the leading industrialists all over Europe. The social idea to ‘ameliorate the condition of the working-class and laboring population… by the provision of improved dwellings, with gardens and open space to be enjoyed therewith’ was put into practice by the cacao producers. They moved their factory in 1879 to the southern part of Birmingham, then a rural area.

George Cadbury (1839 – 1922) bought in 1893 some hundred-and-twenty acres of land next to the factory and planned a model village to house the workforce and called it Bournville. The Bournville Village Trust was founded in 1900 when it comprised some three hundred cottages and houses. The ‘Arts and crafts’ style became a hallmark of many ‘typical English’ villages. A recent survey declared Bournville as ‘quite simply one of the nicest places to live in Britain’. There was no public house, since George Cadbury was a Quaker, who put more emphasis on outdoor sports and walking. The nearby Rowheath Pavilion was built under his supervision.

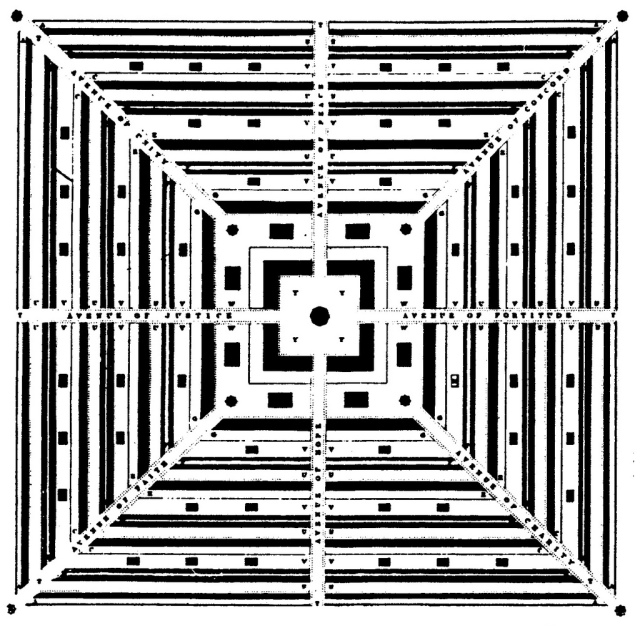

A good example of the influence of higher division thinking on future city design was James Silk Buckingham’s plan for the town of ‘Victoria’, given as the frontispiece of his book ‘National Evils and Practical Remedy’ (1849). The writer had an adventurous life. He went to sea at the age of nine and was captured as a prisoner of war. After a short sting as a book-seller in England, he went to sea again and sailed the Mediterranean as a trader. He visited Egypt, Arabia and reached India after much hardship. Buckingham founded a newspaper in Calcutta in 1818, but his sharp pen brought him in conflict with the government. His eleven travel books are now virtually forgotten, but he is remembered for his Plan of a Model Town (fig. 666). Buckingham’s model town of Victoria, made up of concentric squares, predated Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City movement (1902) and influenced the design of the Australian city of Adelaide.

Fig. 666 – The future city of Victoria was designed by Buckingham in 1849 along the established lines of a labyrinth. The eight main lanes towards the center were named after a hotchpotch of classical and Christian virtues and universal human values like unity, peace, concord and charity.

Buckingham asserted that his scheme was designed to ‘avoid the evils of communism’. This statement is curious, because any thinking about a future city community needs some element of central planning. Every urban development is part of a social statement. A dualistic background can be suspected when terms like centralization and decentralization are used, just like the distinction between rich and poor, organized and unorganized, etc. Buckingham’s Victoria touched the idea of the square city, with its long history (see Chapter 4.1.3.3), but did not add much to the concept.

A more practical approach to future architecture was carried out by Joseph Paxton (1803 – 1865). Paxton became Head Gardener at Chatsworth House (Peak District, Derbyshire) at the age of twenty-three. He developed from there into a creative visionary with his glass buildings (COLQUHOUN, 2003). Chatsworth House was owned by William Cavendish, who had his London residence in Chiswick House (see fig. 421). The Great Conservatory of Chatsworth House started in 1837, following the plans of the architect Decimus Burton (who later worked on the Palm House at Kew). New techniques were used, like steam-driven woodworking machines and standardized components. A second conservatory – the Lily House – was built in 1849 to house the Victoria Regia plant. Both conservatories were demolished in the 1920s.

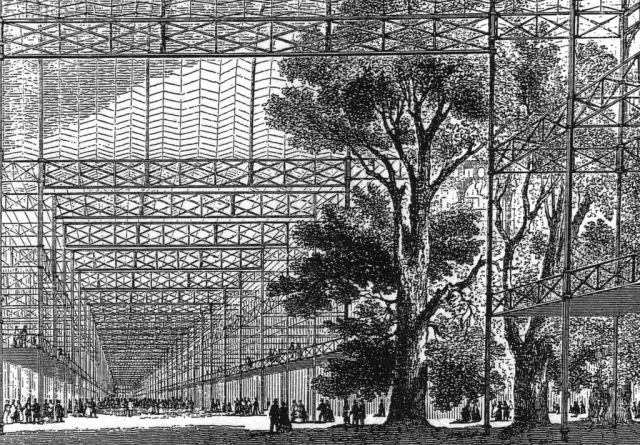

The same fate of destruction was in stock for the Crystal Palace in London, Paxton’s most famous creation for the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park in 1851. The exhibition space covered some 92.000 square meters and the glass and iron structure was 564 meters long and 33 meters high (fig. 667). Crystal Palace was in all sense a futuristic building, which came true. The building was relocated after the exhibition to Sydenham Hill. It served in World War I as an establishment for the Navy and changed thereafter into the first Imperial War Museum. The final blow came on the 30st of November 1936, when a fire left a tangled mess of the Crystal Palace.

Fig. 667 – The Crystal Palace in London was built by Joseph Paxton for the Great Exhibition of 1851. Later it was rebuilt and enlarged in Sydenham Hill, but was destroyed by fire in 1936.

Another futuristic project by Joseph Paxton – which did not materialize – was the Victorian Way of 1855. It was a large glass covered circumference of London, modeled on the Crystal Palace. The initial idea of a passage (gallery street) came from Fourier’s phalanstery, where they were called ‘rues-galéries’. William Mosely’ Crystal Way followed Paxton’s ideas, but was less ambitious in scope.

David PIKE (2005) noted that this covering-up of streets was the necessary foreplay for an enlarged consciousness of urban space in the early twentieth century. It was realized that ‘things can not be created independently of each other in space’ and the metropolitan underworld became part of that concept. The underground railway of the Circle Line is now the visible result of Paxton’s futuristic imagination in the middle of the nineteenth century.

A similar structure of iron and glass like the Crystal Palace was built in Amsterdam between 1855 and 1864 at the Frederiksplein. It was known as the Paleis voor Volksvlijt and burned down in April 1929.

An interesting futuristic city project for New Zealand was started by Robert PEMBERTON (1854/1985), a man who never visited the islands. He was a philanthropist, who lived in London and Paris. His best-known ‘Explanation of The Happy Colony’ dated from 1854, but he wrote several more books and tracts, including ‘An Address to Robert Owen’ (1855), ‘The Science of Mind-formation’(1858) and ‘On the Necessity of Popular Education’ (1859).

Fig. 668 – The Happy Colony of Robert Pemberton was envisaged as a model town ‘to be established in New Zealand by the Workmen of Great Britain’. The plan remained visionary.

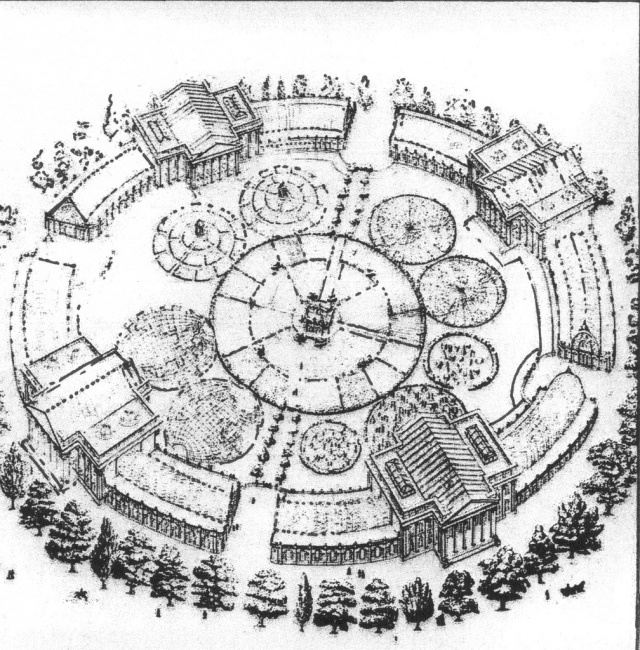

The two illustrations as given in the publication of the Happy Colony in 1854 indicated a circular lay-out (fig. 668/669). This choice was a basic statement against Owens’s rectangular future city. ‘Right angles are opposed to the harmony of motion’, according to Pemberton, ‘and in a town there must be motion’. He was further convinced that the bad formation of towns had an influence on the bad formation of minds.

Fig. 669 – The central part of the Happy Colony by Robert Pemberton featured four colleges. Educational tools, like a world map and one of the universes were laid out in the circular enclosure. The subtitle of Pemberton’s book was given as ‘Dialogues between a philosopher and a learned friend – Address to the workmen of Great Britain – Description of the Elysian academy, or natural university’.

The first circle of the Happy Colony – or Queen Victoria Town – contained in Pemberton’s description four colleges (or Natural Universities) with conservatories and workshops. Manufactories were placed in the second circle and public horticultural gardens occupied the next circle with a large park at the outer rim. The Happy Colonists should adopt a system without a nuisance and ‘all contention about individual property will be for ever done away with’. Concentration of labour, art, science and learning was the main feature of the new establishment ‘so that the divine creative principles – economy of time, labour, and space – will be acted upon.’

The thoughts of future cities took a realistic turn at the end of the nineteenth century when Ebenezer Howard (1850 – 1928) developed his ‘Garden Cities of Tomorrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform’ (1898). The edition of 1902 was called ‘Garden Cities of To-morrow’. This new type of cities did carry a social and political message, which was directed towards the ‘evils of communism’ (like Buckingham’s ideas). The capitalistic landlord, which was seen by Howard as the prime instigator of inner city poverty, would disappear when the local authority took control of the financial side of housing and development (MORRIS, 1997). A decline in population of old city centers would in due course lead to a decline in property values.

Howard’s inventive mind was inspired by a bestseller of the American author Edward Bellamy (1850 – 1898) called ‘Looking Backward from 2000 to 1887’ published in 1888. He bought some hundred copies to distribute them among friends. The book described the history of an upper-class gentleman (Julian West) in Boston, who finds himself in a socialist utopia in the year 2000.

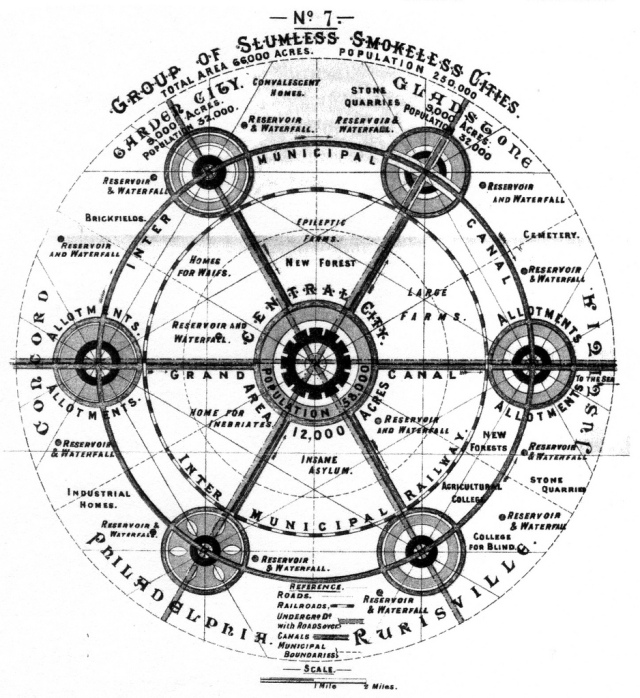

Howard envisaged the town as being influenced by three magnets in which the advantages of city and countryside were combined and the disadvantages eliminated. City development would take place in an orderly sequence. The new towns should be ‘self-contained and balanced communities for work and living’. A network of closely linked towns would be the core of the urban development, following a distinct plan rather than guided by natural growth as a sprawl or undirected spread (fig. 670).

Fig. 670 – This group of ‘slumless and smokeless cities’ were a compilation of the ideas of Ebenezer Howard’s Garden Cities. This map was included in the first edition of Howard’s book in 1898, when it was titled ‘To-morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform’. The illustration was omitted in later editions in favor of the sketch ‘Correct principle of a city’s growth’.

Howard’s visionary plan of a restorative utopia (PINDER, 2005) was to create a Social City with a natural and healthy living space catering for around thirty-two thousand people. If that numbers were reached a second new town would begin. The central city in the circular-hexagonal plan would have a population of around fifty-eight thousand inhabitants.

Howard’s ideas were inspired by a practical mind, knowing that building cities involved a program of land reform and should be cost-effective. The new town authority would acquire land at an agricultural level of land prices and retain ownership of the land. Residents would pay a ‘rate-rent’ to the municipality for their use of the land. Chapter three (the Revenue of Garden City), four (General Observations on its Expenditure) and five (further details of Expenditure) of Howard’s book are all concerned with the financial side of city development. Howard saw material inequality in society as part of the inner city problems.

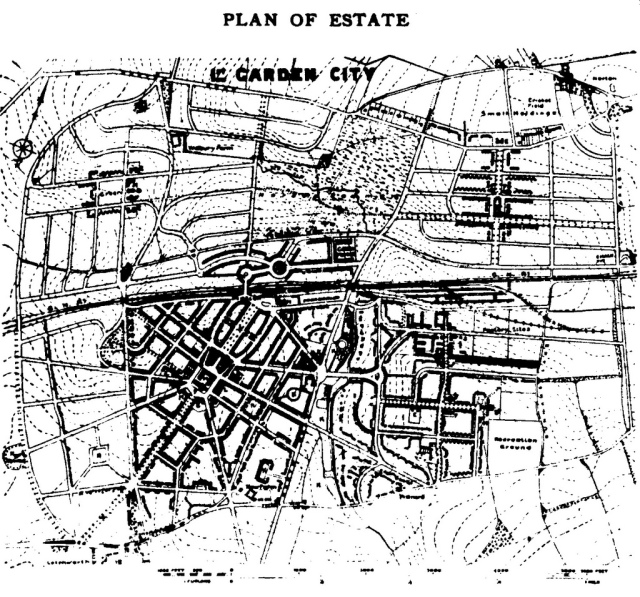

Fig. 671 – This plan of the first ‘garden city’ of Letchworth in Hertfordshire (England) was given by the architects Parker and Unwin in their publication ‘A Guide to Letchworth’ in 1907. Some of Howard’s geometrical formality of a radiating pattern was retained around the town square.

The first garden city was called Letchworth, a town in Hertfordshire, and started in 1903. The architects Ricardo and Lethaby used a variety of radial, square and curved streets, only half-heartedly following Howard’s suggestion of roads following contours in the field. Trees were left standing and no public houses were built (this ban was lifted after a referendum in 1958). The Plan for Letchworth by Parker and Unwin (1907) gives an overview of the radial character of the streets around the town square (fig. 671). The layout of Letchworth Town Square was also published in C.B. Purdom’s The Garden City (1913).

Howard initiated in 1919 the second town called Welwyn Garden City. The concept of a satellite city, as introduced by Raymond Unwin (1863 – 1940), was followed here. The idea of town clusters around Greater London and a Green-Belt principle were put to the test. The rapid increase of motorcars for personal mobility and transport created new problems, which initially could be handled by the Garden City concept. The policy of planned overspill found an apotheosis in Patrick Abercrombie’s ‘Greater London Plan’ in 1944. This influential proposal for the future of London established a model for city planning after the war. The search for locations of the New Towns around London beyond a green belt was on.

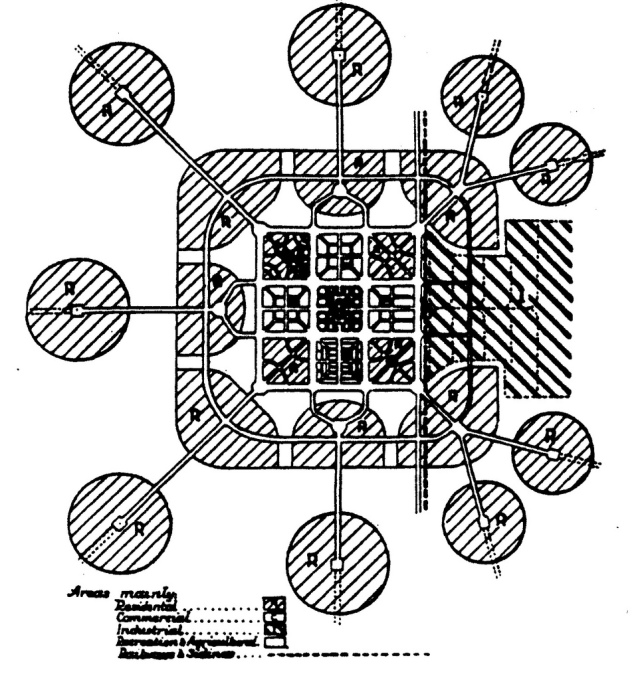

Fig. 672 – The scheme for satellite cities as developed by the architect Raymond Unwin was a popular mechanism in the city planning in Europe in the early twentieth century.

Unwin’s idea of satellite cities (fig. 672) was part of a general move in town planning in the first quarter of the twentieth century (see also fig. 536). A satellite city is different from a suburb, because it has its own facilities and is ‘independent’ of its nearby metropolis. There is, on the other hand, no consensus of what characterizes a suburb, where it stops and where the satellite city starts.

The London-born architect Charles Robert Ashbee (1863 – 1942) was a gay man in a time when homosexuality was illegal. He married Janet Forbes in 1898 and had four children. His contribution to the Dublin town planning competition of 1914 – which was won by Abercrombie and Kelly & Kelly – followed on the teachings of Geddes. Ashbee was mentioned earlier (fig. 167) as an important member of the Arts and Craft Movement. A commission to the palace of the Grand Duke of Hesse resulted in Ashbee’s involvement in the constructions of the Mathildenhöhe in Darmstadt, a project of artists’ studios and houses on the Duke’s estate, which started in 1899.

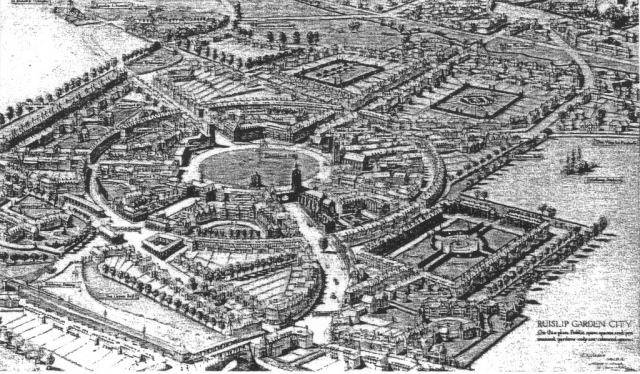

Ashbee published his ideas in a book titled ‘Where the great city stands’ in 1917 (CRAWFORD, 1985). Plans for a co-operative Garden City at Ruislip were incorporated in the book (fig. 673). Ashbee worked for six years in the Middle East (Palestine) for the British Military Government, helping to build a new Jerusalem and lived there with his family until 1923.

Fig. 673 – Ashbee’s view of a future city resulted in a design for the circular town of Ruislip Garden City.

The spirit of future cities found many adherers in the 1920’s and 1930’s in Germany. Paxton’s ‘mythology of glass’, as materialized in the Crystal Palace, was carried forwards by the German architect Bruno Taut (1880 – 1938). The Glass Pavilion of the Werkbund Exhibition in Köln in 1914 was probable Taut’s most noticeable work. He also contributed to the garden cities of Hopfengarten (1911) and Reform (1914/1921) in Magdenburg (Saksen-Alhalt) and Am Falkenberg in Berlin (1914). His Haus der Freundschaft was his submission (in 1916) to a competition for a cultural community centre in Constantinopel (Istanbul) in which the complete German architectural avant-garde participated (Peter Behrens, German Bestelmeyer, Paul Bonatz, Hugo Eberhardt, Martin Elsässer, August Endell, Theodor Fischer, Bruno Paul, Hans Poelzig and Richard Riemerschmid).

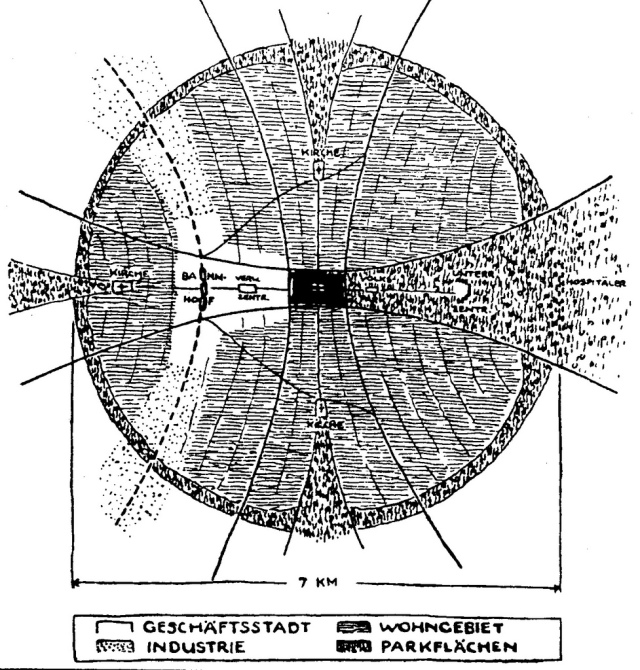

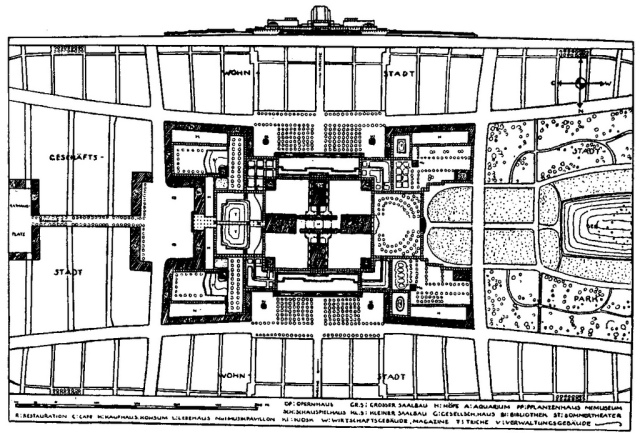

Taut’s futuristic Geschäftsstadt of 1919 is centered on the city crown (‘Die Stadtkrone’) (fig. 674/675). This part of the city is ‘flooded by the light of the sun, the crystal house reigns over everything like a flashing diamond, sparkling in the sun as a symbol of the highest serenity, joy-fullness, and spiritual delight’ (WHYTE, 2003).

Fig. 674 – The futuristic city by the German architect Bruno Taut had a circular shape with the city crown (Stadtkrone) as centre point.

Taut fled Nazism in 1933 and went to Switzerland, where he met with the art historian Sigfried Giedeon (1888 – 1968), the writer of ‘Space, Time and Architecture’ (1943). Later that year he emigrated to Japan and returned to Istanbul (Turkey) in 1936. He ended his life here in 1938 as an exile and was buried – as the only non-Muslim – at the Edirnekapi Martyr’s Cemetery (JUNGHANNS, 1983).

Bruno Taut made in 1918 a set of drawings, which were published in 1920 as: ‘Die Auflösung der Städte oder Die Erde eine gute Wohnung oder auch: Der Weg zur Alpinen Architektur’ by Folkwang Verlag (Hagen/Westfalen). This series – commonly known as ‘Alpine Architecture’ – made an artistic statement and became his principal theoretical work (SCHIRREN (2004). He reconstructed – in five parts and thirty drawings – a fantastic and utopian world. The first part (Kristallhaus), in four folios, depicted a Crystal Building. The second part was concerned with the shapes of the mountains in general. ‘Grotesque Regions’ in Switzerland (Matterhorn, Monte Rosa) were drawn as valleys with glass buildings and mountain tops with arches.

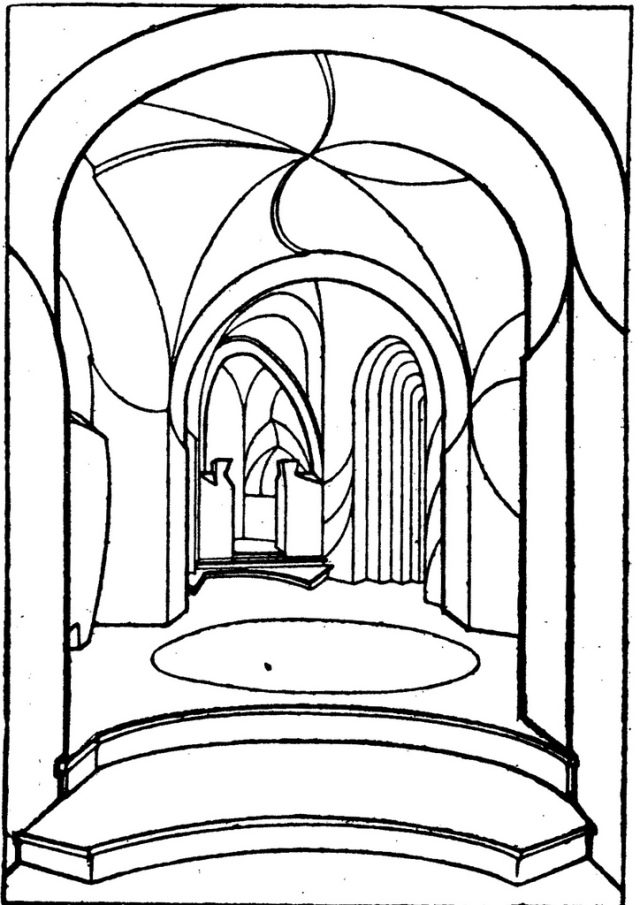

Fig. 675 – The City Crown was the central part of a project, drawn up in 1915/1916 by Bruno Taut as a vision of a future city and published in 1919 as ‘Die Stadtkrone’.

The third and main part of the series deals with ‘Alpine Building’ in Switzerland (Upper Engadin), Austria (Tyrol) and Italy (Dolomites and Lake Lugano). His ‘Appeal to the Europeans’ (Plate 16 of 30) gives a map of the areas of interest and a text written to form a cross. This symbol of Christ’s Passion contains, according to Matthias Schirren, the underlying moral message of ‘Alpine Architecture’. The fourth part of the series has to do with the earth’s crust building (Erdrindenbau). The Ralik and Ratak Island (the Sunrise and Sunset islands, part of the group of twelve hundred Marshall Islands in the South Pacific) – which were claimed by Kaiser Wilhelm II to counteract the ‘Yellow Peril’ – were represented with garlands-like lines. The island of Rügen in the Baltic Sea was adorned with ornamental structures like arches, spines and crystals. It is not clear what these repre-sentations had to do with the earth crust except some abstract notion of a ‘living earth’ – the earth as an organism.

The last part of the ‘Alpine Architecture’ is concerned with speculative ‘astral building’. A cathedral star (Domstern) looks like a cosmic theater in a crystal surrounded by comets and stars, which seems to rotate around a vertical axis. The influence of the poet and philosopher Paul Scheerbart (1863 – 1915), who also composed aphoristic poems about glass architecture for the Glass Pavilion, was eminent in this drawing. Taut’s image of the Solar System is probably the most elaborate and complex drawing of the sequence. The text ‘the spheres, the circles, the wheels’ pointed to a dynamic culmination of a cosmic experience. Some sort of cyclic consciousness comes into view here.

The final sheet (Ende) only gave the following text: ‘stars, worlds, sleep, death, the great, nothing-ness, the nameless, end’. The words seem to indicate, in their Romantic setting as used by Taut, a vague reference to a Buddhist’s Nirvana. The quadralectic interpretation would place these exclamations in the invisible invisibility of a First Quadrant (I) and ‘the end’ can be experienced as a void (between the communication cycles) in the final part of the Fourth Quadrant (IV).

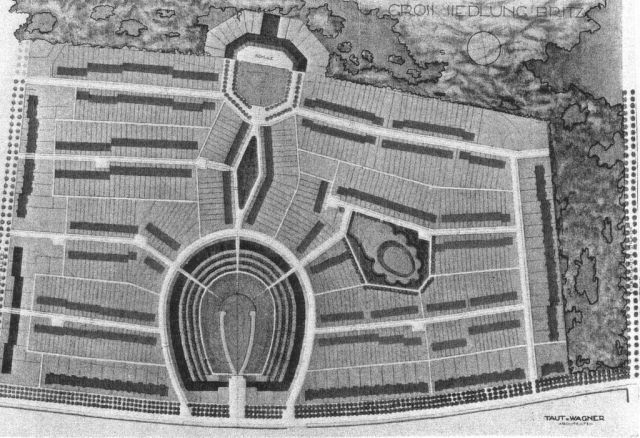

Taut did not really improve – with his sketches in ‘Alpine Architecture’ – on his ideas of the Glass House in 1914. His expectations might have been too high-strung at a time of recuperation after the war. However, his contribution to Modernist architecture in general is still considerable. His horse-shoe housing project in Berlin-Neukölln (fig. 676) – the Britz Horse-shoe Settlement (1925 – 1929) – reflected, according to Schirren (2004, p. 19) the principles explained in Alpine Architecture: ‘that of an empathetic interpretation of naturally existing forms on the part of an architect whose mind is receptive to the omnipresence of oppositions in nature’. This point of view is derived from lower division thinking, which could be right in Taut’s case.

Fig. 676 – The horseshoe shaped housing development Britz in Berlin-Neukölln was one of the works of Bruno Taut, which was executed between 1925 and 1929.

Housing development Britz in Berlin-Neukölln (Photo: Marten Kuilman, Oct. 2010).

An evaluation of Taut’s work in quadralectic terms does not give abundant evidence of his mind entering into higher division thinking, except maybe his early work in the Glashaus (1914) and Die Stadkrone (1919). The Alpine Architecture has five parts and no hint to tetradic features. His publication of a futuristic ‘Haus des Himmels’ – presented in a newspaper supplement called ‘Frühling’ (Spring) in 1920 – used the triangle/hexagonal shape. Taut emphasized that ‘die heiligen Zahlen 7 und 3 verbinden sich in ihm zur Einheit’ (the holy numbers 3 and 7 are connected in the building in unity). The horseshoe plan of 1925 was original, but with little reference to the four-fold.

The Modernist spirit of the early twentieth century found in Italy a strong and awkward supporter in Filippo Tommasso Marinetti (1876 – 1944). His ‘Manifesto of Futurism’ was launched in the French newspaper Le Figaro in 1909. Its message called for the glorifying of war – seen as ‘the world’s only hygiene – militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of freedom-bringers, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and scorn for women’ – and the destruction of ‘museums, libraries, academies of every kind and a fight against moralism, feminism and every opportunistic or utilitarian cowardice’.

Marinetti was one of the first supporters and members of the Fascist Party under Benito Mussolini. This attention to war and violence, which came so closely related to the Futurists’ movement in Italy, is – in quadralectic perspective – a sign of a Third Quadrant mentality showing its (ugly) face in the Second Quadrant of ideas, the conceptual place where futuristic cities are born.

Drafts of a futuristic city (La Città nuova) were produced by Antonio Sant’ Elia (1888 – 1916), a Como-born builder, draughtsman and architect. His graduation project in Bologna dealt with monumental cathedrals, which could be approached by long flights of steps. Some spectacular drawings of high-rise buildings were shown at an exhibition of the Nuove Tendenze group at the Famiglia Artistica in Milan together with Mario Chiattone (1891 – 1957). The latter wrote books – The Building of a Modern Metropolis and Bridge and Studies of Volume – and shared a studio with him. A drawing of soaring towers that touched the sky and rooms that were only three feet wide was another of Chiattone’s contributions to early Futurism. Multiplicity gone wild was the name of the game here. Sant’Elia launched in the same year (August 1914) his ‘L’architettura futurista’ (Manisfesto of Futurist Architecture) in the newspaper Lacerba.

Sant’Elia was killed in 1916 in one of the skirmishes between the Austro-Hungarians and the Italian armies along the River Isonzo in present-day Slovenia, but his fame as a Futurist remained. His imaginary buildings were vast with an emphasis on horizontal and vertical lines. Modernity and progress were visible in the lifts on the outside of the building and different levels of road users. Later architects like Le Corbusier picked up his messagio. There are no indications that this short-lived Italian futurist had an inclination towards higher division thinking and his frantic search for identity (nationalism) rather points to the opposite.

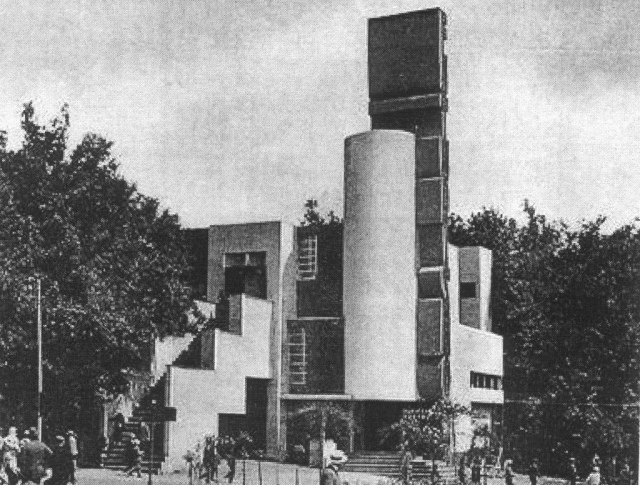

Enrico Prampolini (1894 – 1956) was a painter, sculptor and designed decors as a scenographer. He had to leave the art academy in Rome after writing a futuristic manifest (1912), which was followed in 1924 in his ‘Manifesto dell’art meccanica fururista’. He had connections with Theo van Doesburg and the Dutch De Stijl group and other representatives of the European avant-garde movements like the Dadaists, Der Stürm, the Novembergruppe and the Bauhaus. His Futurist Pavilion at the exhibition held in the Parco Valentino in Turin (1928) is a mature example of futuristic architecture in a concrete form (fig. 677).

Fig. 677 – The Futurist Pavilion at the exhibition in the Parco Valentino in Turin (1928) was designed by Enrico Prampolini. It marks, together with the War Memorial in Como, a highlight of Prampolini’s contribution to Futurist architecture.

The architect and scenographer Virgilio Marchi (1895 – 1960) met Marinetti during the First World War in 1916. Futurists’ ideas had reached a stage of self-confidence by the time Marchi’s book ‘Archittettura futurista’ (1924) was published. Marchi was a prolific essayist, theoretician and teacher and gave a vision of buildings as ‘habitable sculptures’ rather than concepts of the ‘machine for living in’ of the Rationalists. Fig. 678 is a good example of such an approach, leading to a superb use of space.

Fig. 678 – The Bar of the Casa Bragaglia by Virgilio Marchi (Rome, 1921) was a statement of architectonic futurism, which proved feasible and found its subsequent followers.

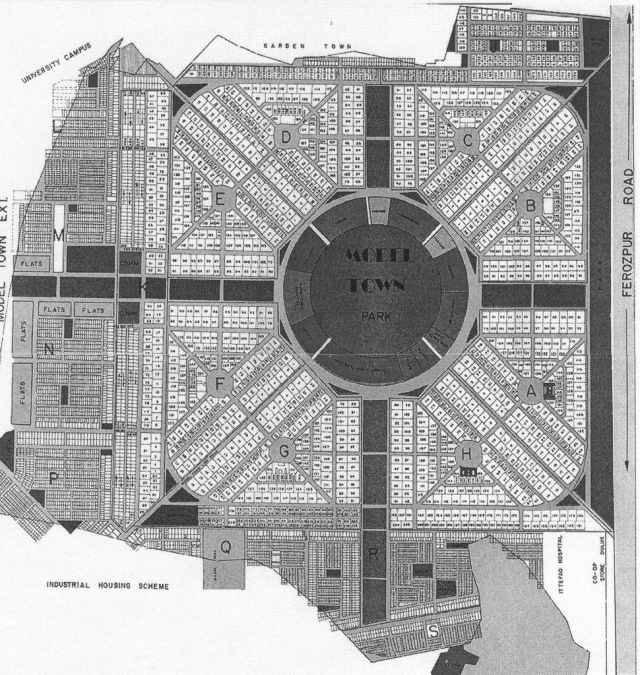

The time of the Interbellum was fruitful for daring developments in other parts of the world as well. For instance, an ambitious planning project was realized in the Model Town, situated in a suburb of Lahore (Pakistan). This new town was established in 1921 and followed a cross-and-circle in a square lay-out (fig. 679).

Fig. 679 – This map of Model Town in a suburb of Lahore (Pakistan) was given by Estateman Properties International in Islamabad and shows a cross and circle in a square. The community was started in 1921 by Dewan (prime minister) Chem Chand as a cooperative based on the principles of self-help, self-governance and cooperation. Eight smaller squares (A – G) are the centers of the local community blocks with their own market, play grounds and mosques. The city has a total population of about 100.000. The circular Model Town Park was built in 1990 and is one of the largest public parks of Lahore. Barriers are placed at the entrances, which are closed after 9 pm and only four entrances are open at night.

The cooperative principles – which are still in force today in the Model Town – were first popularized by George Jacob Holyoake (1817-1906), an English social reformer. He was the last person to be convicted for blasphemy and spent six months in jail. Soon thereafter he coined the term ‘secularism’ in 1846 and described it as ‘a form of opinion, which concerns itself only with questions, the issues of which can be tested by the experience of this life.’ Secularism, as a doctrine, can be described as ‘any philosophy, which forms its ethics without reference to religious dogmas and promotes the development of human art and science’.

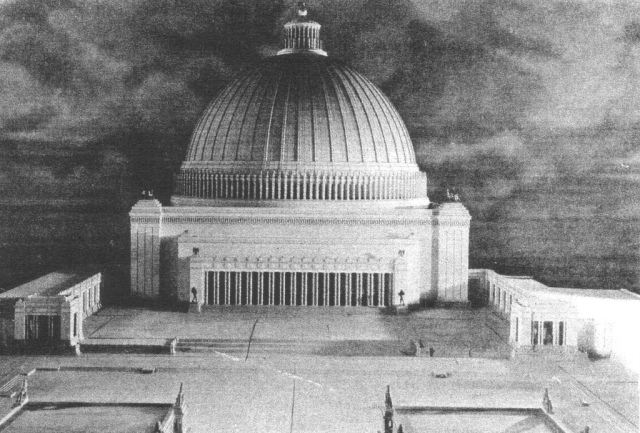

A last upsurge of futuristic city inspiration in Germany took place during World War II, when the architect Albert Speer (1905 – 1981) – following Hitler’s concept – featured a Grand North-South Boulevard with the Arc of Triumph and the Great Hall of the Reich (fig. 680) as part of a renovation of Berlin. Adolf Hitler’s envisaged a modern Berlin, called Welthauptstadt Germania (World Capital Germania), as a city full of marble architecture, ‘which would be comparable with the achievements of the Egyptians, Babylonians and Romans’. His endeavors added little to the historical role of architecture as an artistic adventure, except perhaps the size of the buildings and squares. The domed Great Hall was supposed to accommodate a crowd of hundred-and-fifty thousand people.

Fig. 680 – The Great Hall of the Reich, as planned by Albert Speer, was supposed to be the centerpiece of a reshaped Berlin, called Germania. The megalomaniac building, with its marked dual symmetry, was never built. The aesthetic vision of the Nazis (and Hitler) was born in oppositional thinking, and did not reach above a level of long straight boulevards and Triumphal Arches.

The development of future cities in America was initially incorporated in the growth of urban life the United States-as-a-whole. In other words, the cities in the young country were developing so fast, that many ideas of ‘future’ towns were realized straightaway. The architect Frank Lloyd Wright (1867 – 1959) submitted – in ‘The Ladies’ Home Journal’ of July 1901, featuring an enormous artillery gun on its cover! – a design for ‘suburban houses which can be built at moderate costs’ and proposed a Quadruple Block Plan. This basic plan of small square blocks of four equal-sized lots – surrounded on all sides by roads – surpassed the traditional practice of lot allocation. The title of the 1901-article ‘A Home in a Prairie Town’ resulted in the name ‘Prairie Style’ for the residential houses, which were designed by Wright in the period between 1901 and 1917. The Robie House, built in Chicago in 1909, can be seen as the masterpiece of the prairie style, showing the ‘open plan’ to the full.

Fig. 681 – A plan for a subdivision of a typical development lot by Frank Lloyd Wright, 1913. The quadruple block planning on an urban scale was directly derived from the large grid patterns, which divided the country as soon as colonization had set in. However, the tetradic concept – here in a checkerboard pattern – was enhanced with non-symmetrical variation of housing blocks and parks.

The quadruple ideas were expanded in the ‘City Club of Chicago Land Development Competition’ in 1913. The Quadruple Block Plan included now several social levels and had the amenities of a small city (fig. 681). The decentralization was further emphasized in the Broadacre City design, first presented in an article in The Disappearing City in 1932 and constantly being revised up to the large foldout in full color in ‘The Living City’ (WRIGHT, 1958).

This project – executed in the second half of Frank Lloyd Wright’s career – displayed a future city with weird towers and airplanes. This science-fiction type of vision did not add to a practical urban development. His students constructed a scale model in 1932 at Taliesin, Frank Lloyd Wright’s estate in Spring Green, Wisconsin. It was explained on a map published in ‘When Democracy Builds’ (1945). The plan indicated four square sections (A – D) of minimum houses surrounded by little farms, medium houses, vineyards and orchards, a tourist camp, small industries, an airport, a circular arena and larger houses.

‘The broad acre city, where every family will have at least an acre of land, is the inevitable municipality of the future . . . We live now in cities of the past, slaves of the machine and of traditional building. We cannot solve our living and transportation problems by burrowing under or climbing over, and why should we? We will spread out, and in so doing will transform our human habitation sites into those allowing beauty of design and landscaping, sanitation and fresh air, privacy and play-grounds, and a plot whereon to raise things’.

This quotation (WRIGHT, 1932/1935) conveyed a message of expansion as the final solution for a congested inner city. Mobility was celebrated as a panacea against the ills of overcrowding. This remedy can be placed in the context of the American culture, which reached a decisive stage around 1890 (see fig. 551 and fig. 619). The young cultural entity experienced in that year its First Major Approach (FMA), which implied a first proof of its real existence, expressed in low CF-values (CF = 6). America shaped – unknowingly – its identity at that very point of the communication (with a twenty-first century, European observer).

The last decade of the nineteenth century were frantic years of expansion and building. The skyscraper became the hallmark of America, a type of construction, which was never tried before on such a scale in any known civilization. The first skyscraper – the Home Insurance Building – was built in 1884 using a structural steel skeleton as its frame and lighter masonry walls were ‘hung’ from the steel framework like curtains.

Soon a dispute on this type of building arose when a Minneapolis architect named Leroy S. Buffington was granted a patent in 1888. He proposed a twenty-eight story ‘cloud-scraper’ (or stratosphere-scraper), which was ridiculed by the architectural press of the time. Chicago architects started a campaign to discredit Buffington, with the aim to avoid paying royalties. Their argument was that the idea was already tried in the Home Insurance Building (the building was demolished in 1931). They were successful, partly because Buffington damaged his cause by forging dates on his drawings to predate 1885.

The Equitable Life Assurance Company Building on the corner of Broadway and Cedar Street (near Wall Street, Manhattan) in New York is probably the first high-rise commercial building with all the technical factors – like a structural system, elevators and utilities, as researched by transdisciplinary scholar Carl W. Condit (1914 – 1997). This building was completed in 1870 with seven-and-a-half stories. This possible candidate to be the first real skyscraper was destroyed by fire in 1912, but left its mark as a turning point in American cultural history. The revolutionary moment was the introduction of the first elevator. Life insurance was a relatively new product in America and had to be introduced in a spectacular way with maximum publicity. Therefore, a competition for the design of the building (in 1868) had only one requirement: the building should include a passenger elevator. Many prominent architects took part in the contest.

This radical novel idea of an elevator created a major psychological shift in the valuation of multi-storied buildings. The top floors of buildings were historically regarded as less attractive, because the flights of stairs required physical effort. Subsequently, lower rents were received from the upper floors. The elevator changed all this. Suddenly, the top stories were more valuable (with higher rents), away from street noise and towards the light. Therefore, the Equitable Life Assurance Company Building and its elevator opened a psychological domain, which can hardly be exaggerated. Suddenly, a new type of stairways to heaven was opened, and people with power and influence were only too willing to go that way.

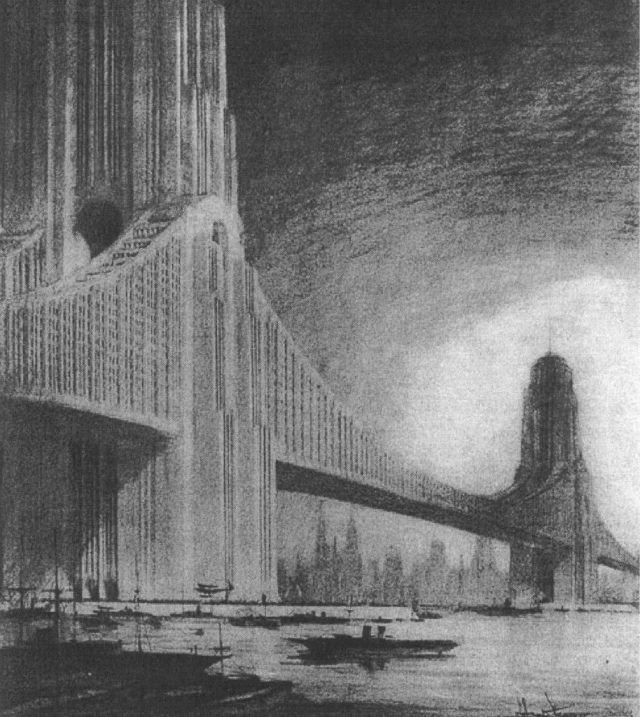

A real conjurer of cities of the future in America was Hugh Ferriss (1889 – 1962), an architectural draftsman and architect born in St. Louis. He made, as a ‘delineator’, a great number of perspective drawings of buildings with dark and moody appearances (fig. 682). The Avery Drawings and Archives of the Columbia University Libraries has most of his drawings stored, which are accessible on their online catalog CLIO.

Fig. 682 – This typical Hugh Ferriss drawing, from his book ‘Metropolis of Tomorrow’ (1929) gave a view of apartments on bridges in a dramatic setting.

The (dualistic) theme of light and dark was mastered by Ferriss to the extreme. His visualization of the city environment as a drama, hungry for emotional responses, placed him in a Fourth Quadrant setting, despite the use of Third Quadrant techniques. This cross-border movement (between quadrants) is at the heart of any creative process.

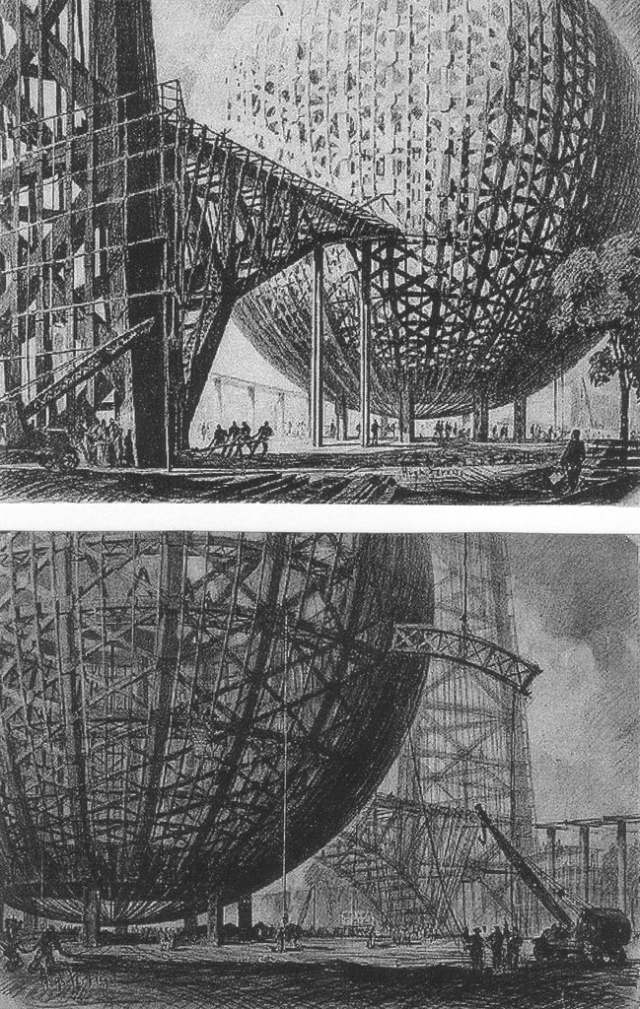

Ferriss was involved as a planning consultant at the World Exhibition in New York between 1936 – 1939. Some of his most expressive work was generated in this period, with huge circular structures as its hallmark (fig. 683).

Fig. 683 – These graphic perspective drawings by Hugh Ferriss of large perispheres at Flushing Meadows were made for the New York World’s Fair 1939 – 1940. The Trylon and Perisphere were the highlights of this most memorable world’s fair ever held.

Ferriss’ drawing of the Johnson Wax Administration Building in Racine (Wisconsin) – which was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright – is another possible indication of his (later) interest in the circular rather than the linear (fig. 684). The Johnson Wax Administration Building was a truly futuristic creation at the time (1936 – 1939). The construction of the dendriform columns in the Great Workroom caused controversy with building regulations and was only allowed after a test of one of the columns. The calyx could hold some sixty tons of materials. Wright added later (in 1947) a fourteen-floor Research and Development Tower to the complex, with no visible support under the outer walls. A bridge, consisting of plate glass and glass tubing, connected the buildings.

Fig. 684 – This drawing by Hugh Ferriss of the interior of the Johnson Wax Administration Building in Racine (Wisconsin) was made circa 1941. This structure, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, is a futuristic premises come true.

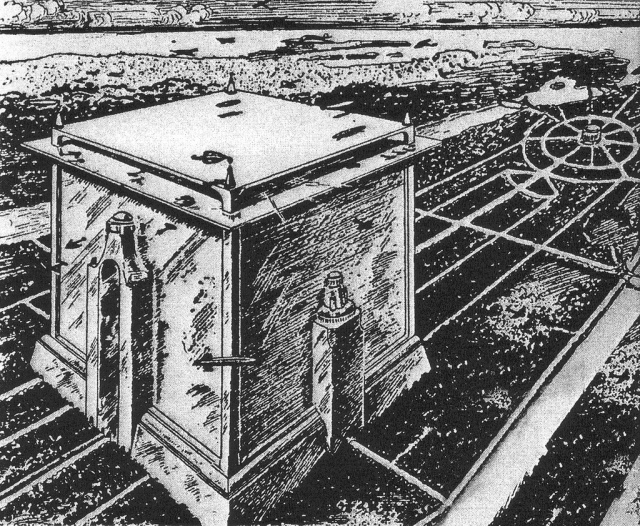

A lesser-known futuristic city in the shape of a cube was created by the Reverend Louis Tucker. He was inspired by descriptions of the Bible (Revelation 4: 6-8) to create his utopian world (fig. 685). His story, as described in the magazine ‘Science Wonder’ (Sept. 1929), is part of an upsurge of fictional writings and fantastic pictures in the early decades of the twentieth century. The French novelist Jules Verne (1828 – 1905) might have started this trend in the middle of the nineteenth century when a sense of unlimited travel mesmerized the public – if only as a means to escape from the times of turmoil, war and economic depression. Science fiction has since that time created a virtual world, which heavily drew on imaginative draftsmen like Ferriss.

Fig. 685 – The Cubic City was proposed in 1929 by Reverend Louis Tucker with the intention to stack a whole city, like New York, into a cube. A true miracle would be necessary to bring this science-fiction world into reality.

The 1920 to 1930’s were also the years of great futuristic projects by French and Russian architects, who were earlier encountered in relation to the superquadras in Brasilia and the city development of the Russian (de)urbanists (COOKE, 1995).

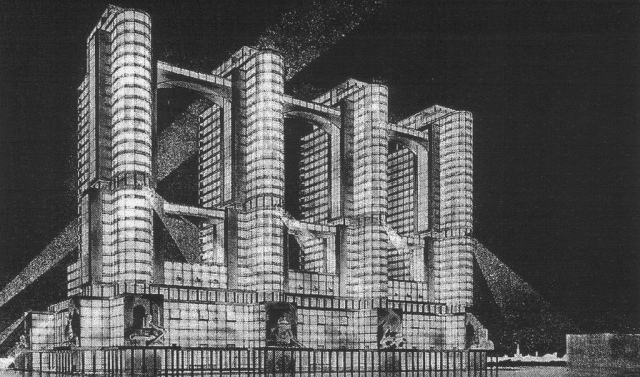

Fig. 686 – This design in a NKTP Draft contest by the Vesnin Brothers (1934) is a grandiose example of futurist architecture.

The Swiss architect Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris (1887 – 1965), who named himself Le Corbusier, was possibly the most prominent representative in France, while Nikolai Ladovsky (1881 – 1941) can be regarded as the great Russian avant-garde architect. The latter designed a new curriculum for the Moscow School of Architecture (called OBMAS or United Workshop), emphasizing that the architect’s material is space, not stone. One of OBMAS’ graduates was Georgy Krutikov (1899 – 1958), the author of the ‘Flying City on the Aerial Paths of Communication Communal House (1928), a utopian city in the sky.

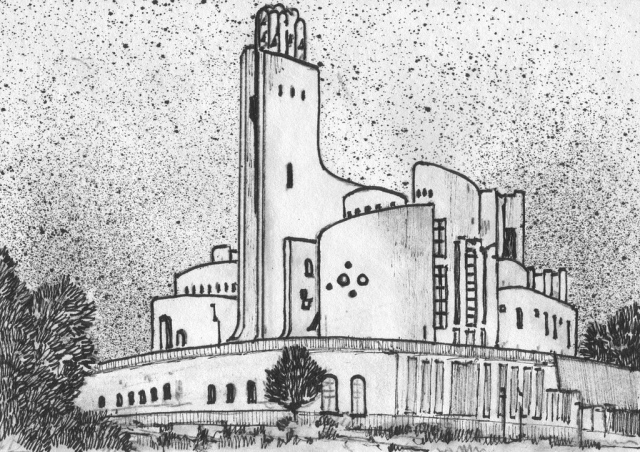

The Narkomtiazhprom (NKTP) was an architectural contest in 1934 for the Commissariat of Heavy Industries, to be constructed on the Red Square in Moscow. Some of the contestants included Ivan Leonidov (1902 – 1959), Konstantin Melnikov (1890 – 1974), the Vesnin Brothers (fig. 686) and Ivan Fomin (1872 – 1936). This spirit of futurism (and associated escapism) was kept alive in Russian architecture. It did not get the worldwide attention at the time (like Le Corbusier) due to the restricted nature of the Communistic government. However, a building like the ‘Palace of Marriage’ in Tbilisi (Georgia) had all the characteristics of real futurist architecture (fig. 687), just like the ‘Roads Ministry’ (1975) in the same city. The Polytechnic University in Minsk (Belarus, 1981) and the Druzhba Holiday Center Hall in Yalta (Ukraine, 1984) are some samples of innovative types of architecture in more recent times.

Fig. 687 – The ‘Palace of Marriage’ in the Georgian city of Tbilisi is a good example of the many ‘futuristic’ architectural projects, which were realized in the Soviet period in Russia (Drawing by Marten Kuilman).

Badri Patarkatsishvili, a local business tycoon, bought the state-owned Wedding Palace in 2002, and turned the building into his home and campaign headquarters. It became a ‘Palace of Solemn Ceremonies’ again (in 2008), after Patarkatsishvili’s death in Britain.

Le Corbusier proposed, after his formal statements for a new architecture in his book ‘Vers une architecture (1923), a ‘Plan Voisin’ (1925) for Paris. His (idealistic) aim to change the minds of the captains of the car industry (Paul Citroen and Louis Renault) failed, but the aircraft company manager Gabriel Voisin (also a director of a car manufacturing division) was prepared to pay for the plan’s printing and exhibition costs. The PlanVoisin involved a total restructuring of Right Bank of Paris (La Defense) with large cruciform towers.

His ‘Contemporary City’ or ‘City for Three Million People’ consisted of an orthogonal street grid with park space (fig. 688). This future city was much criticized and never reached reality, but his fundamental ideas about mass-urbanization generated inspiration for many architects in decades to come. Le Corbusier’s La Ville radieuse (The Radiant City) of 1935 showed some changes in (social) conceptions. The central district of the Radiant City is now residential and class-based stratification is abandoned.

Fig. 688 – The ‘City for Three Million People’ is a megalomane project by Le Corbusier in a futuristic setting. The cruciform, central office blocks are surrounded by blocks of flats.

An evaluation of the futuristic work of Le Corbusier and his Russian contemporaries is not easy to make. A comparison (analogy) with another historical visibility might shed some light here. It is evident to a present-day observer that the period from 1910 to 1935 is extremely important in the history of architecture, due to its futuristic element. This time span (1910 – 1935 = CF 7.30 – 6.50) in the European cultural history is situated in the first part of the Fourth Quadrant (IV, 1 – see also fig. 267) and can be compared to its Roman counterpart (see fig. 88). The same CF-values (7.30 – 6.50), if transferred to the Roman cultural era, correspond to the years 217 – 238 AD.

This epoch of the Roman Empire started with the assassination of Emperor Caracalla (217 AD) in Syria and covers turbulent times. Emperor Macrinus was murdered in 218. Emperor Elagabalus, who established a Syrian sun god (El Gabal or Baal) as a major Roman god, was murdered in a latrine in 222 AD. Alexander Severus became Emperor and had to fight a war with the Sassanid dynasty of Persia (230 – 232 AD) and led campaigns against the Alemmani (233). The ‘crisis of the third century’ started when he was murdered by his troops in 235 and lasted until 268 AD (CF 6.60 – 6.72). These CF-values of the Roman cultural period are comparable with similar values of the period between 1932 – 1972 in the European history. The Second Major Approach (SMA) – which is the (second) moment of ultimate truth in a communication – can be pinpointed at 250 AD in the Roman and at 1950 AD in the European cultural history.

The most recent future city in America was probably created by Walt Disney (1901 – 1966) in the middle of the twentieth century in his ‘Epcot Center’. EPCOT stood for the Experimental Prototype City of Tomorrow and was a larger and more elaborate version of Disneyland – which was first built in Anaheim (Los Angeles, 1955) and later as Disney World in Orlando, Florida (1971).

The idea of a fun park for the people was inspired by the famous Tivoli Park in Copenhagen (Denmark), which opened on August 15, 1843 and is the oldest amusement park in the world. The motto of the creator of the Tivoli Park (Georg Carstensen, 1812 – 1857) was ‘when the people are amusing themselves, they do not think about politics’. Theaters with music, gardens, restaurants, amusement rides and merry-go-round were the main constituences of the park.

The EPCOT in Florida would be an American interpretation of these same human interests, which included golf courses and resort hotels. Disney did not live long enough to see his dream come true, but his contribution to a new community remained intact. The Epcot Theme Park is now one of the four parks of Walt Disney World resort and is divided into Future World and World Showcase. The former focuses on technological advancements and innovation. Spaceship Earth in the form of a giant golf ball is the icon of the theme park. Disney’s architectonic achievements had a touch of fairytale Romanticism, with an eclectic use of past styles and geared towards the fantasy world of children.

The Future City will be left behind here. The promise of a better future is enclosed in its boundaries and time will tell if the visions of today can stand the rigor of progress. The future will be a playground for the distinctions of division thinking. In the end – and even at the beginning – there are four Future Cities with their own characteristics. (I) The first will be a future city, which is never seen. The second (II) is a future city, which will linger on as an idea. The third (III) is a future city, which becomes reality. Finally (IV) there is a future city in a quadralectic setting, in which its various disguises are understood.

Pingback: Реконструкция Вселенной: Футуризм | Tanya Melamori

Pingback: On the Plaza: The Politics of Public Space and Culture by Setha M. Low – SCULPTURE

Pingback: Charles Fourier and the Theory of Four Movements | Equivalent eXchange