The grid city can be found on all continents and is embedded in many different cultures. The Chinese grid cities were already partly covered in the present book under the heading of the ‘square’ cities (Chapter 4.1.3.3). Many square cities – but not all – were also grid cities, as could be seen in the reconstruction of the old capital of Xi’an (or Chang’an, in the Shaanxi Province) in the T’ang Dynasty (618 – 907 AD, see also fig. 564).

The square and grid theme originated in the Zhou (Chou) dynasty (1123 – 256 BC), although some sources put the tradition as far back as the fifteenth century BC. The first written form was in the ‘Kaogong ji’ (Record of Trades) section of the Zhou li, an Eastern Zhou text originated in the Spring and Autumn Period (722 – 475 BC). It said that ‘a capital city should be square on plan. Three gates on each side of the perimeter lead into the nine main streets that crisscross the city and define its grid-pattern. And for its layout the city should have the Royal Court situated in the south, the Marketplace in the north, the Imperial Ancestral Temple in the east and the Altar to the Gods of Land and Grain in the west’.

Mexico City in Middle America is probably the biggest grid city in the world. Its pedigree is indigenous (before 1500 AD) with further development (of the grid pattern) in the Spanish colonial period and a continuation after the country (Mexico) became independent in 1810 (and its recognition by Spain in 1821 after Agustin de Iturbide rode into town as the ‘National Liberator’).

The history of the foundation by the Aztecs (in 1325 AD), its destruction in 1521 and rebuilding by the Spaniards and its subsequent development in the nineteenth century, marked a long line of urban planning with the grid as its guiding principle. Further explosive urban growth in the twentieth century – from some five hundred thousand inhabitants in 1900 to nearly nine million in 2008 – saw the appearance of the shantytowns, the chaotic conglomerates of makeshift houses (see Chapter 4.1.1).

The grid design was highly popular in South America, from ancient time onwards. The city of Chan Chan, once the capital of the pre-Inca Kingdom of Chimor, near Trujillo (Northern Peru), is an example of city planning along rectangular lines. The period of building was estimated between AD 950 and 1400, and some two hundred thousand people might have lived there at one time.

Chan Chan covers about 28 square kilometers and comprises at least nine self-contained, walled-in units (‘citadels’ or ‘palaces’), in a rectangular grid structure. The vast site was put on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1986 and also on the additional ‘in danger’ list, because the adobe (mud) is vulnerable to excessive precipitation. The ancient city is now in ruins and restoration is a difficult process. The nearby ‘pyramids’ (temples) of Huaco De La Sol and Huaco De La Luna were made by people of the Moche culture between the first and eight century AD and deserve preservation as well. Recently, a mummy of a woman was found (c. 450 AD) in a tomb near the summit of Huaca Cao Viejo in El Brujo, south west of Chocope, in the Ascope province (one hour drive from Trujillo).

The Law of the Indies was codified by Philip II in 1573 to provide a formal framework for the colonial urbanization processes, and kept in force for some three hundred years. The Law specified a square or rectangular central plaza with eight principal streets running from the plaza’s corners. This design pattern, which was in line with the practices of earlier Indian civilizations, was followed by scores of communities throughout Middle and Southern America.

The city of Lima, the capital of Peru, followed a traditional development just like Mexico City from a pre-Inca background into a Spanish colonial town – founded by Pizarro in 1535 as ‘Ciudad de los Reyes’ – with a continuing urbanization after the independence of Peru was declared in 1821 and consolidated after the Battle of Ayacucho in 1824.

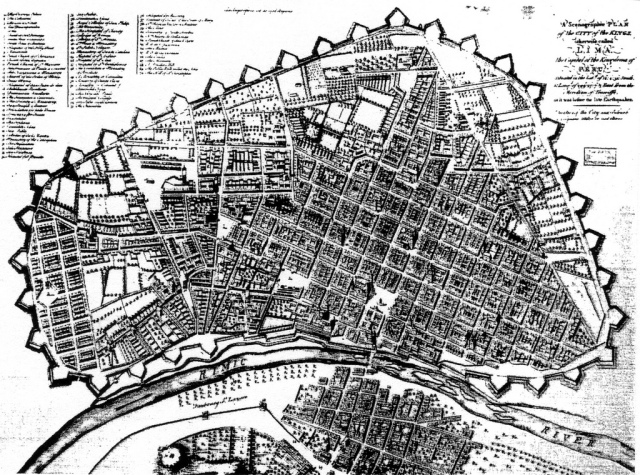

Figure 620 gives a plan of Lima in the year 1683. It displays a walled city with the majority of the houses in a grid pattern, but also some radiating structures. Lima became the major export town of the Spanish colonial trade (gold and silver). A map of 1750 by the famous French cartographer Jacques Nicolas Bellin (1703 – 1772) still indicates the same outlines. The main city and its harbor port Callao were connected by urban development in the 1970’s. The whole coastal area from Callao to Chorrillos in the east is now covered by housing developments in alternating grids.

Fig. 620 – The plan of the city of Lima in 1683 gives an example of post-Hispanic city development in South America, consisting of radial and grid elements. The north is towards the left-hand corner at the bottom of the page.

Cuzco, in the southeastern part of Peru, was the Inca capital of the Tahuantisuyu (‘The Land of the Four Corners’). Popular belief and local lore tell the story that the city was planned as a puma (jaguar), with two sectors: urin and hanan. These areas were in turn divided into four parts representing the four provinces: Chinchaysuyu (NW), Antisuyu (NE), Cuntisuyu (SW) and Qollasuyu (SE). The leaders of these provinces could only live in that particular quarter of the city, which corresponded to their part of the empire.

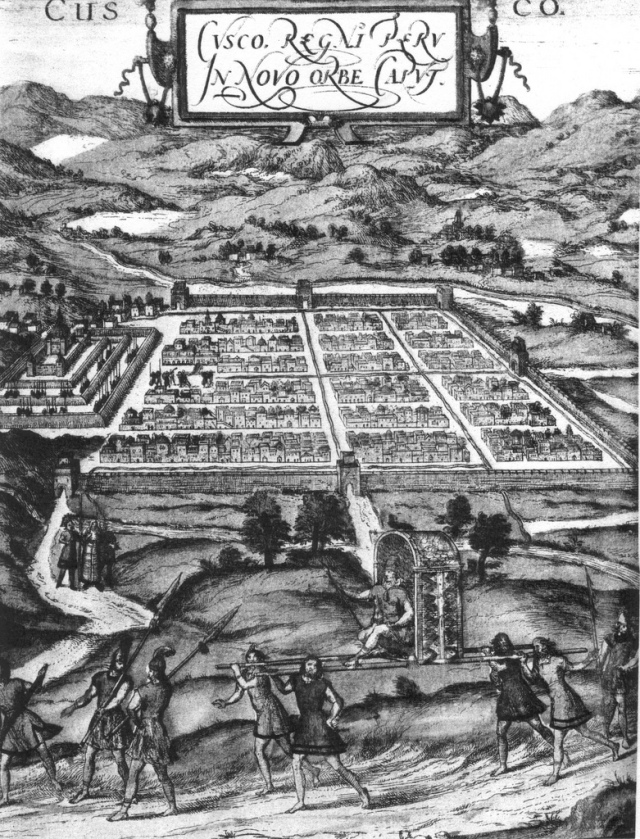

It is unlikely that the initial settlers had a jaguar in mind, but certain geometric directions might have crossed their mind when they started building their houses. Sometimes the imagination of (pseudo) archeologists led them into observations, which are debatable, but wins them the favor of the public. The bird’s eye view of Cuzco, as given by the German cartographers Georg Braun and Frans Hogenberg in their atlas ‘Civitates orbis terrarum’ (Cologne, 1597), is fairly idealistic (fig. 621). The first Latin edition of Volume I of the ‘Civitates’ dated from 1572. The woodcut is admitted to Antoine Du Pinet (1564) after a plan in G.B. Ramusio, Navigatione (Vol. III, 1556). The map could be seen as a projection of ancient European myths and utopian dreams. The map of Tenochtitlan (Mexico) is given in the same work of Braun and Hogenberg and was discussed earlier. The topography around Cuzco only allows for a rather crude ‘traza’ (regular checkerboard pattern) with the plaza major (Plaza de Armas) in the center.

Fig. 621 – A grid map of the city of Cuzco (Peru) – as given here in a later edition of Braun and Hogenberg’s book ‘Civitates orbis terrarum’ (1597) – is an idealistic representation of the situation as the Spanish conquistador Francisco Pizarro (1476 – 1541) found the city during his 1533 expedition to Pachacamac.

Many other South American cities, like Caracas (Venezuela, founded in 1567), Buenos Aires (1580) and Mendoza (1561, with a rebuilding after the 1861 earthquake, which killed five thousand people) in Argentinia, started as a grid city and continued to use the rectangular pattern in their extensions in later years.

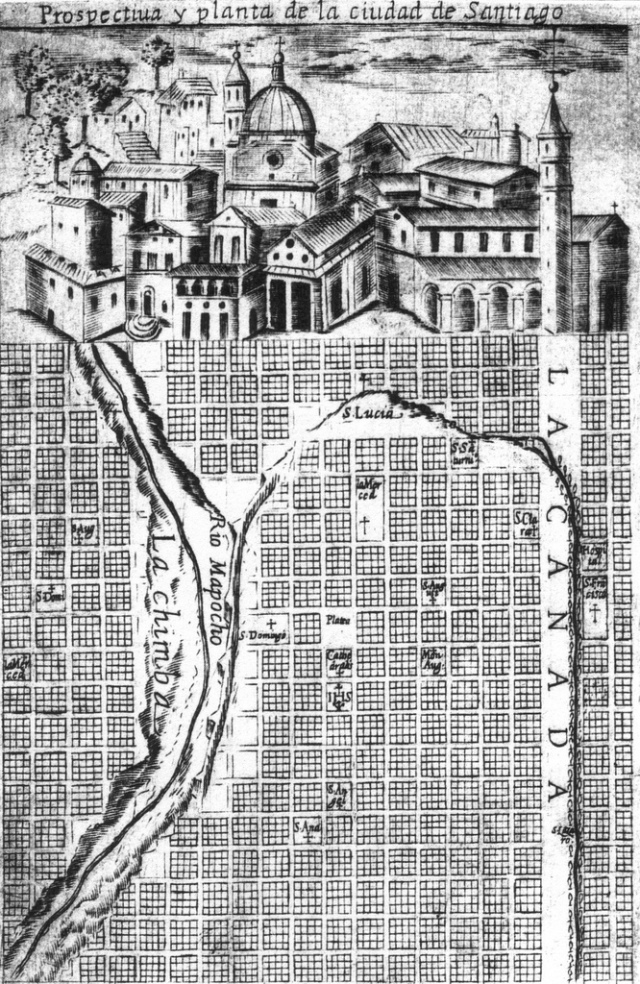

The last example will be Santiago, the capital of Chili, which was founded in 1541 by the Spanish conquistador Pedro de Valdivia (c. 1500 – 1553) at the foot of the Santa Lucia Hill, formerly known as the “Huelén“. Valdivia became the first royal governor of Chile. He was murdered at the end of an extraordinary eventful life. The city was planned according to the traditional Spanish checkerboard layout (fig. 622).

Fig. 622 – This engraving of the city of Santiago in Chili was given by Chilean Jesuit and chronicler Alonso de Ovalle (1603 – 1651) in his book ‘Histórica relación de Chile’ (Rome, 1646). The publication in Rome was staged in order to avoid Spanish censorship.

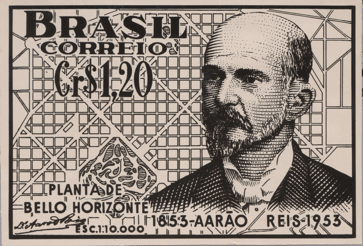

More modern developments, like Belo Horizonte (Minas Gerais) in Brasil, still uses the grid as a structural element in urban development. The first planned city in Brasil (founded in 1897) had two oblique crossing orthogonal schemes designed by Aarão Reis in 1894 (fig. 623). The ideas were partly borrowed from Washington DC and comprise the eclecticism of the time. The symmetrical blocks had to be a physical expression of the slogan ‘order and progress’ – written on the Brazilian flag as ‘ORDEM e PROGRESSO’ – and any memory of the baroque colonial style was erased.

Fig. 623 – A stamp to commemorate the hundred’s birthday of Aarão Reis, the engineer who conceived the city plan of Bello Horizonte (Minas Gerais) in Brasil in 1894. In addition, a portion of his grid plan of the city at a scale of 1: 10.000 is given.

Later, in the 1940’s, the young architect Oscar Niemeyer added the Pampulha Neighborhood to the capital of Minas Gerais (commissioned by the mayor and later president of Brasil Juscelino Kubitschek). Both men – Niemeyer and Kubitschek de Oliveira (1902 – 1976), together with Lucio Costa – wrote architectural and planological history in 1956 with the foundation of the new capital Brasilia.

The former casino in Belo Horizonte/Pampulha (1942; now an art museum, since gambling was no longer allowed) is situated above the artificial Pampulha Lagoon, and was the first example of Modernism in the country. Niemeyer followed the concept of Le Corbusier’s promenade architecturale, a journey through a building in order to reveal the soul of the building. The garden was designed by the Brazilian landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx (1909 – 1994).

Finally, the many grid cities of Australia can be mentioned, like Adeleide on a map by P.F. Sinnett (1881) (given in: GALANTAY (1979), which followed the North American type of urbanization. The country is still too young to opt for a separate ‘cultural period’, apart from their Aboriginal past. The same lack of cultural context holds for the modern grid patterns in the cities in South East Asia and elsewhere.